| |

„We shared everything – our worries, every scrap of food – and we tried to keep each other´s hope alive.” |

How Gisela Stone and her friend Francis survived the Kaufering XI and Kaufering I Concentration Camps.

|

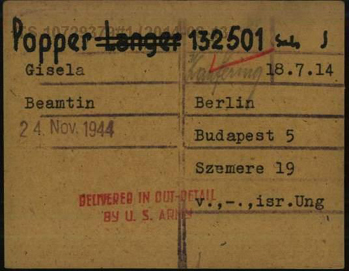

It is already dark on the evening of the 21 November 1944 when the women, exhausted and starving, arrived at the assembly ground of the Kaufering XI Concentration Camp. The glaring beams of the camp searchlights blind their tired eyes. In front of the primitive earthen huts stand the female concentration camp guards with their dogs. The animals strain at their leashes, barking at the new arrivals with barred teeth. The women must surrender their personal possessions. Refusal to do so is punishable by death. The women lay all their remaining belongings on the ground and move over to the other side of the assembly ground. The guards have almost a hundred women to process. They are tired and sick of this work. Gisela Stone (Gisela Popper) and her friend Francis (Franziska Steiner) already have a long road of suffering behind them and they have learned "never, ever to be one of the first.” They therefore position themselves at the back of the crowd and when their turn finally comes, they receive a terse instruction from the guards to “Carry on!” The concentration camp inmates stand freezing and hungry in the cold night. Everything has been taken from them. Their family, their possessions, their human dignity and their identity. They no longer have names, they are only numbers. Gisela Stone receives the number 132501. Finally, the new arrivals are assigned to the dirt-covered huts.

"They were half submerged in the ground, only had a small roof and had wooden – I don´t know what they used to call them –it was just a piece of wood, where we could sit or lie, covered with a thin layer of straw. It was very hard.”

At about noon all the female inmates has to assemble for roll call. Most receive a small bowl or container. They receive something to eat and have to endure the salutation: “This will now be your food, you dirty Jewish pigs. This is all you will be getting from now on, until you fall down dead.”

They feel wretched and downcast. Many weep in despair when the guards declare that this ration will be distributed only once a day. “It was nothing, when one thinks that what we got barely resembled gruel, but was disgusting and watery, and a piece of so-called bread, which was rather sawdust. We were so hungry, tired and sick that we would even have eaten a rat when we were able to catch one.” The women comfort one another, and even though none of them know what the future will bring, they try to make the best out of their situation. When they are allowed to return to their huts, they collapse exhaustedly into a deep sleep.

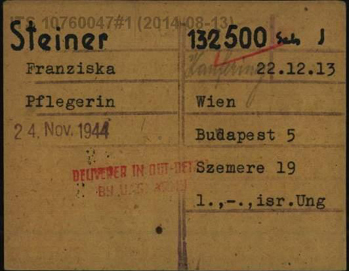

Gisela Stone was born in Berlin in 1914, where she spend a happy childhood and youth. Her parents were Hungarian Jews. In 1934 she met and married another Hungarian Jew. She misinterpreted the “dark clouds” on the political horizon. She thought like a German and could not imagine that anything could happen to her, as a member of the middle classes. In 1939, when the situation became critical, the young couple decided to move to Budapest. They were penniless and they had to live in poor conditions in furnished rooms. Young Gisela found employment as a seamstress. Her husband was conscripted for a labour team and was forced to perform heavy road construction work. Later he was sent to a labour camp. Gisela was relocated to the Ghetto. There she experienced heavy Allied air raids. During this time she first heard of Auschwitz. “We heard from people who had escaped from a concentration camp that most Jews were being deported to Auschwitz. Naturally we did not believe this, because we were Germans. We would never be sent there!” In 1944 she first heard of the concept of “extermination camps.” Gradually she began to believe the stories she was hearing. Then the Ghetto was cleared. She had already packed her belongings and was waiting to be evacuated. During this time, she got to know a young girl called Francis, with whom she was sharing a room. The two became friends and stuck together through thick and thin. When there was a knock on the door one morning at 6am, both of them knew that they were being evacuated. The transport was being assembled in a disused brick factory in Budapest. Women of all ages, including pregnant women were rounded up. It is the beginning of November, damp, misty and cold. The two women are freezing, hungry and confused.

Around midday, the women are provided with buckets of drinking water. They drink some and get bad diarrhoea. The marching column then sets off. At night, they camp on open ground. There is no shelter, just woollen blankets. “We covered ourselves with the blankets, but because it was raining, the blankets became heavy and wet, so that we had to lay them aside. Finally, in our small containers that we always carried with us, we received a little soup of indeterminable origin. However, we were happy to have something to line our stomachs with. There were no toilets – nothing. Some of the women in our transport, there were about 1000 of us, still had their periods. It was a desperate situation.”

The next day they march until 6pm in the evening. They are freezing and hungry. Their feet swell up so much that they are no longer able to take off their shoes. “After the third and fourth day, because of the agitation and suffering, no one had their period anymore. Those who marched at the back of the column, who sat down for a moment´s rest were screamed at: “Those who fall behind will be shot.”

Many women, especially the older ones, are shot. So it continues for four more days. When the women reach the Danube, they are allowed to wash themselves. The water is freezing cold and an icy wind is blowing. Then on the fifth day, they reach the border. They are counted and loaded into cattle trucks, 60 per truck. This is where they see the first German soldiers. Amongst them are young lads, no more than sixteen or seventeen years old. They are armed with guns and shove them into the railway trucks. None of the women know where they were headed. Many believe that they were being sent to Auschwitz and are expecting to be killed. “Of course there were no toilets – nothing. We were filthy, full of excrement and some of the women, about five in my wagon, went mad and began attacking us.” After a few hours the train stops at a small station. The women receive water and something to eat. “After we had eaten we all became very calm. We then heard that there was bromine in the food, to sedate us.” The journey continues. The women have to stand the entire time and some of them break down. During the journey, Gisela peers outside from time to time. She is the only one in the waggon who can speak German and reads the names of the towns they pass. She recognises many of the names and is overjoyed, because she knows that this meant they are not headed for Auschwitz. The women´s hope is renewed. .

After a few days in Camp XI, the inmates are assigned to work details. Gisela Stone, prisoner 132501, has to haul stones from one side of the camp to the other. When she is finished, she has to bring them back again. The work is futile and Gisela can not see the point of it. Her friend Francis can speak Polish and this enables her to make contact with some Polish Kapos and arrange jobs for both women in the kitchen. There they spend the whole day peeling potatoes and helping with the preparation of food. “Every day we got the same food when we returned to our barracks between 6 and 7pm: just a little water and this disgusting soup, in which a few potatoes floated. The Kapos ensured that the soup was ladled from the top. They kept the food for themselves.”

|

|

Registration Card of Gisela Stone (Popper) (International Tracing Service (ITS) Bad Arolsen |

Registration Card of Franziska Steiner (International Tracing Service (ITS) Bad Arolsen |

The women become weaker and weaker. They think that they will soon die. The roll calls now take place during the night, every two to three hours, and every time they are counted. They get hardly any sleep.

“When one is in this condition, the only thought one has is: where can I get something to eat. We got diarrhoea because we drank water which wasn´t clean. It never seemed to end. We had no toilet paper of course. At this time it was already autumn, or rather the beginning of winter and as soon as we were able to work outside we collected fallen leaves to enable us to clean ourselves somewhat. In the camp there were no toilets, only latrines. That is how we lived – filthy, bloody, and full of excrement – and we tried to clean ourselves a little. Two German soldiers always stood in front of the latrines. I think that they were so nauseated that they could no longer look at us.”

After two months, Gisela Stone became ill. Pneumonia. She was moved to the infirmary hut. This usually meant certain death in a concentration camp. She had a high fever, no medication and nothing to drink. She was weak and lay most of the time in delirium. She had no idea what was going on around her. Other inmates stole her rations. Francis was on a work detail outside the camp. Late in the evening when she returned to the camp, she self sacrificingly shared her meagre rations with her sick friend. “After my exhausted friend returned to camp and shared her little food with me, she stayed with me in the infirmary hut. Because we were crawling with lice, she spent the night scratching my back and my head. There were three different types of lice: head lice, lice in the intimate areas and lice in our clothing. We teemed with them. It was terrible and I was sure that I was not going to make it.”

Francis knew the doctor responsible for the infirmary hut from Budapest. She wanted to prevent at all costs that her friend be sent to the Infirmary Camp. She knew that this would mean certain death for Gisela. She still had a small knife in her possession which she had managed to smuggle through all the inspections, by hiding it in her bosom. She used this to threaten the doctor and intimidate her. Gisela stayed in the infirmary hut and was not transported to the Infirmary Camp. A guard took pity on her and gave here some of his food ration. With time Gisela´s condition improved, she survived the illness.

”There was a time of de-lousing which meant that we were finally able to get rid of these pests which plagued us terribly. We had to go into a building which they called a “shower” and from the ceiling came alternating boiling hot and icy cold water. We were given a type of soap that they had made from the dead – from the bones of our dead.”

Shortly after, the camp was quarantined because of a typhus outbreak. The German soldiers and the camp guards were afraid of infection and tried to stay as far away from the camp inmates as possible. The inmates no longer went to work and the food rations became smaller from day to day. However the daily roll calls still took place. “One day the Camp Commandant asked over the loudspeaker: “Who here speaks German and can type and take shorthand in German?” I had learned never ever to volunteer myself for anything, but this was my chance. I stepped forward and said: “Here!” The Commandant looked at me and pulled a face – I can still remember his face clearly – he thought that I must have been lying. At his side stood a very good-looking German soldier. He was, as I later found out, the Hauptsturmführer (Captain) and was the doctor responsible for all the camps and various things outside the main camp. He stepped forward, examined me and asked: “Do you speak German, can you type and take shorthand?” I looked him in the face and answered “Yes!”"

After this Gisela heard nothing from the Commandant for a long time. Her friend was very worried. She thought that no good would come of it. Two weeks later Gisela was fetched by a guard and brought to the camp Commandant. “I was really scared because I thought that perhaps he was going to punish me or something. Francis began to cry and thought that this was the end. She said: If you go away and they do something to you, I´ll kill myself.” This was not unusual in the camp; it was a daily occurrence. Many people died by running into the barbed wire and committing suicide.”

Gisela was brought to the Camp Commandant; her heart was pounding in her throat. Her fear proved to be unjustified. She was given a typing and shorthand test. She had to take down a dictation from a current article in the “Völkischer Beobachter". From this she learned that the American forces were advancing, which gave her new hope. To her great joy, she passed the test. “I was called and told by the Hauptsturmführer; “Tomorrow you will be deloused. You will receive new clothing and transferred to Camp I.”

When she told her friend, Francis became hysterical. She did not know what she would do without Gisela. Gisela decided to stay with her. When she was called for delousing, she refused to go and was called to the Camp Commandant. He asked Gisela if she knew what it meant to refuse to obey an order given by a German soldier. She said: “Yes, I know what it means, but I have a sister here (meaning Francis). When she cannot be with me, then I no longer want to live. I don´t care what happens to me.” The Camp Commandant bellowed that she would probably be shot. “I don´t care. My life is not worth anything anyway.”

“About a week later I was called again to the Camp Commandant. You can imagine how my friend and I felt. We cried the whole time and said our goodbyes as we thought that I would be getting shot. I went there once again and I was very, very scared. Never in my life before had I experienced such fear, but I really didn´t care. I had no idea if any of my family was still alive, my husband, and my parents. When I entered the office of the Camp Commandant, Hauptsturmführer Blanke awaited me. He looked at me and said. “For a little girl like you (I am short and only 1,59m tall), you certainly have a lot of spunk”, and winked at me briefly. In this moment I had the feeling that I had won.”

Francis was allowed to accompany her friend. Both of them received new shoes and clothing. The next day they walked to Camp I. It is a long way. When they arrived there, they were immediately sent for delousing. “We were the only two women amongst 100 men who were being deloused along with us – they would never turn the equipment on just for us. We stood there. They gave us a towel and we covered ourselves, although we did not have much left to cover. We were so malnourished that we weighted not more than 90 pounds.” Two guards brought Gisela to the infirmary for German soldiers, outside the camp. In the office there, she was to produce transcripts of the “Völkischen Beobachter." This allowed her to receive the latest news from the front. She was very hungry but received nothing to eat and was worried about her friend who she heard nothing from the whole day. In the evening, around 6pm she was brought back to the camp. Finally she received something to eat – watery soup with bitter turnips. The Kapo, a female inmate separated the two friends and assigned them places at opposite ends of the hut. Francis was of the view that this was done only out of spite. She complained, but the Kapo made it clear that she was in charge and did not elaborate further.

The next morning Gisela was ordered to report once more to the infirmary. “They brought me several books and told me that I was now responsible for keeping the lists of the deceased. The people who had died the previous day were officially listed, by means of their prisoner number and date of death, and this was reported either by a Kapo or by a German soldier on a sheet of paper. I had to list them in a book. There were many, about fifty per day.”

When she returned to the camp in the evening, she found her friend Francis is tears. She was at the end of her strength. The Kapo had assigned her to a work detail which had to perform heavy road construction work. Francis had received nothing to eat all day, and dressed in her thin clothing, was forced to work outside all day in the snow and rain. The pair were in despair. Gisela tried to help her friend. “The next day I talked to the Hauptsturmführer. Where I got the courage from to approach him, I do not know. I was weeping and could not work. He asked me what was wrong. So I told him what was happening with my friend. I told him that she had nothing to eat and was being badly treated by the Kapo. At the distribution of food the Kapo never ladled her the food from the bottom of the pail, giving her only hot water, and treated her brutally. Hauptsturmführer Blanke calmed me and promised that he would deal with the matter. He went to the Kapo in the camp and – he always had a small whip which he kept in his boot. I cannot think what happened there, but Francis told me that he approached the Kapo with his whip in his hand, ready to whip her. Whether he did or not I can no longer remember. The next day Francis was transferred to the SS kitchen detail. I don´t even need to say how significant that was."

Francis helped in the SS kitchen, scoured the huge pots used for preparing food for the SS people and the sick soldiers. Every now and then, she was able to smuggle leftover food to her friend. “Of course there was always the opportunity for her to bring me something because the kitchen was outside the camp and Francis has to pass the window of the office where I was sitting and typing. She made a sign; I stood up, left the room and met her at the latrines. There she always pulled out something from under her arm or from between her bosoms. But then I saw the others. They were in a pitiful situation and starved to the bone. All over the camp they were dying, one after the other. They were all starving! It was exactly at the time when we had a great many rural Jews, who refused to touch this terrible piece of so-called bread. They simply ate nothing. After a week passed, they were no longer with us. The only ones who were better off were the Kapos.”

The part of the camp were the women were housed was separated from the rest of the camp by barbed wire. This was usually the case in the Kaufering/Landsberg Concentration Camps where male and female inmates were imprisoned together in the same camps. The women’s camp was a camp within a camp, with its own roll call ground and earthen huts. An architectural peculiarity, which only occurred in the Landsberg camps were the special barracks, which had domed roofs assembled from French clay cylinders. This type of earthen hut, which was only used in the women´s barracks, was somewhat more comfortable than the other more primitive earthen huts and were found in Camp I as well as Camp VII. In comparison to the earthen huts, this form of accommodation was dry and comparatively warm. The female inmates were assigned all sorts of work details. They were forced to perform heavy physical work and endure terrible human suffering along with their male counterparts. They hauled heavy sacks of cement, pushed wagons, loaded and unloaded wood or iron and worked on building sites, building camouflaged structures. However, the women did not only work on building sites and in the camp. There were many work details consisting especially of women who worked in and around the city of Landsberg. Young women with shaven heads, dressed in the blue striped uniform of the concentration camp were regularly seen cleaning the Landsberg Railway Station. Others peeled potatoes in Landsberg restaurants, whilst some were forced to help bring in the harvest on local farms.

In the camp, the female concentration camp inmates were humiliated and physically abused. Even the camp commanders had no qualms about participating in the abuse. Pregnant women, when they were no longer able to hide their condition, were sent to Auschwitz in so-called “disabled transports”, where they were murdered. If a prisoner was guilty of “racial defilement”, she was beyond help. She could expect no mercy.

The Jewess Fritzi Kohn fell in love with a camp guard and became pregnant. She was transferred to Dachau and was hanged in the courtyard of the crematorium. Her naked body was left hanging on the gallows as a warning to other prisoners. Emil Mahl, the hangman of Dachau said in his affidavit during his criminal prosecution in Dachau:

„I have an especially good memory of the execution of the Jewess Fritzi Kohn. She was sentenced to death for racial defilement. The accused was forced to fully undress in the gas chamber. At first, she balked at appearing naked in front of the many men present. She was then brought with force out of the gas chamber by the SS-Hauptscharführer, Kuhn and Boettger. She attempted to cover herself with her hands. This evoked laughter and obscene jokes from the SS members present. She was then made to stand on the trapdoor and I put the noose around her neck.”

In the meantime, the surrounding countryside around Camp I had come under a number of bombing attacks. The prisoners did not know who carried out these air raids, as the aeroplanes flew so high that it was impossible to see their markings. Roll call no longer took place every day and the women had to carry out their work in the dark, damp earthen huts. They were not allowed to leave their huts – even to use the latrines. For this purpose a pail was placed in the corner which had to be used by all 60 women. One of them was always responsible for emptying the pail. Gisela had the opportunity, now and again, to listen to the radio. A soldier allowed her to. Because of this, she knew that the American Forces were very close. This gave the women hope and courage. One day the International Red Cross arrived at the camp. Small parcels were distributed. Amongst the vital foodstuffs contained in the parcel were hard to digest items like sardines in oil. The weakened bodies of the prisoners were not able to stomach such things. Many prisoners ate the entire contents of the parcel, out of fear that the items would otherwise be stolen by other prisoners. They became terribly sick.

Gisela Stone was still working in the office of the infirmary. During air raids, she remained there alone. The soldiers fled to a nearby bunker. She used the opportunity to help herself to tonics and vitamin tablets. These helped keep her and her friend alive.

It is April. The food rations are getting smaller and smaller. Even the guards no longer have enough to eat. Sometimes the sick soldiers in the infirmary share their food with Gisela. They have no appetite and are happy to give something away. “All these things helped us to survive. I still remember how someone gave me a small apple. Of course, I shared it with Francis. We shared everything – our worries, every scrap of food – and we tried to keep each other´s hope alive. We feared that the bombing raids would cost us our lives.”

By the end of April there were air raid allarms occurring every two hours. The guards were scared and there was absolute confusion. “Hauptsturmführer Blanke came into the office and stated: “It will not be long until you are free!” And he asked me what my name was: We had no names there and were always called by our numbers. I said: “My name is Gisela.” He said: “Now Gisela, you will not have to wait too long and then you will be free.” I did not believe what the man was saying as we were all distraught. We did not understand anything which came from the mouth of a Nazi. I described this friendliness, this small bit of friendliness to my friend Francis. She did not believe it either. The next day when I reached the office outside the camp, the death books which I administered had disappeared. I asked about them and I was told that they had been burned. Chaos reigned, the soldiers were running here and there and they no longer knew what was going on – of course they told me nothing. Hauptsturmführer Blanke came once into the office and brought me a pound of butter – I had not seen butter since 1938 and it was now 1945 - and his daily ration, and wished me luck. Later, in the afternoon I heard from the soldiers, who were very bewildered and did not know what was going to happen to them, that he had shot himself. He and his young wife had committed suicide. They had a small daughter there, maybe four or five years old. He did not kill her.”

The two women wanted to make use of the general state of confusion and decided to escape. They did not succeed and they were loaded into one of the trains “evacuating” concentration prisoners from the approaching American troops. The intended destination of the train was Austria. The train started moving. When it reached the town of Schwabhausen, a huge air raid occurred.

“We were attacked by low flying planes and our train stopped in the vicinity of another train standing at another platform. It was full of ammunition. I think they thought that it would be hit by the Americans and the whole thing would go up in smoke. When the air raid began, the soldiers were all running back and forth, confused. Francis and I and five others – they were men- jumped out of the train and ran – we ran for our lives into a nearby forest. The bullets were flying over our heads, they were shooting at us. However, it was dark and they could not see us. We disappeared into the woods. Of course we had nothing to eat and drink and only the clothes on our back. It was bitterly cold – it was the end of April and the weather was dreadful. In the wood, we all collapsed together; we all lay down – while they shot over our heads. It was guns from the other side. But we heard nothing, we were too exhausted and really shaken so that no soldier, no concentration camp, no barbed wire existed for us anymore. We just wanted to survive. The next day the sun shone brightly – I still remember that well – and because I was the only one who could speak good German, they sent me out of the woods to see what was going on. I met a woman – she had obviously not noticed my clothes, otherwise it would have been clear that I was a concentration camp prisoner – and she called to me: “Don´t go that way, the Americans are already there!” Well, that is all we needed to know. We stood up, as hungry and tired as we were, and began to march out of the woods. Once we were out, we saw a large number of tanks coming towards us from the opposite direction. We did not know what to do. The men said we should raise our hands above our heads and walk on with hands up. We did this. When the tanks came nearer, they saw our tattered shapes and turned off. So we walked on. We walked to a small village called Penzing. Even while still outside the village, we noticed that white flags were flying from many of the houses and we knew that the town must have surrendered. Just before the village, at a small gasoline station, we came across the first American troops. When they saw us, at first they did not believe who we were. Clearly, they had not yet heard much about the camps. When they realised, they immediately reached into their pockets and gave us their rations. I will never forget this moment as long as I live. We were free!”

It is not known how many female prisoners survived the Kaufering/Landsberg Concentration Camps. The dead lie buried in mass graves around Landsberg. The most important document which would have given us this information are the death books which Gisela Stone was forced to administer, but which were burned during the last days of the war.